The mallard is a large dabbling duck native to much of Europe, Asia, and North America. It is one of the most common and recognizable ducks in the world. It got its common name from the Old French word mallart or malart which means “wild drake.”

In North America, mallards are found across much of the continent, from southern Canada to Mexico and from the Atlantic to the Pacific coasts.

In Europe, mallards are found throughout much of the continent, from Scandinavia to the Mediterranean and from Britain to the Russian Far East.

In Asia and Africa, they are found in parts of Japan, China, and Southeast Asia, as well as in parts of the Middle East and North Africa.

The mallard is a member of the genus Anas, which includes all ducks except for the screaming shelducks and the blue-winged teal. Within this genus, the mallard is most closely related to the American black ducks and the Eurasian teal.

Mallards are highly adaptable and can thrive in various environments, contributing to their widespread distribution. They are also known to be able to hybridize with other closely related duck species, which can also contribute to their genetic diversity and ability to adapt to new environments.

Mallard Duck Scientific Name: Anas platyrhynchos

Height: 50–65 cm (20–26 in)

Wingspan: 81–98 cm (32–39 in)

Weight: 0.7–1.6 kg (1.5–3.5 lb)

Taxonomy & History

The mallard has a long and interesting evolutionary history. It is believed to have evolved from a group of ducks that inhabited much of the Northern Hemisphere during the late Miocene and early Pliocene epochs, about 5-10 million years ago.

During the Pleistocene epoch, which began about 2.6 million years ago, the mallard underwent a series of evolutionary changes that allowed it to adapt to a wide range of environments and climates.

One of the most notable evolutionary changes included the development of its characteristic green head, which is thought to have evolved as a way to blend in with the surrounding vegetation and avoid predators.

The mallard has also undergone significant genetic changes throughout its evolutionary history.

For example, it has a high level of genetic diversity, which is thought to be the result of a process called hybridization. This occurs when two closely related species interbreed, resulting in the exchange of genetic material and the creation of new, genetically diverse offspring.

Physical Description

The adult male mallard, in breeding plumage, is a striking bird with a colorful and distinct appearance. The most prominent feature of the male mallard is its dark, iridescent-green head and a bright yellow bill with a black nail.

The gray body is adorned with a purple-tinged brown breast and a white collar, which stands out against the rest of the bird’s plumage.

The male mallard also has a black rear with white-bordered dark tail feathers, giving it a sleek and elegant appearance. The wings are a mix of gray upper wings with white-bordered blue speculum and whitish underwings, adding to the bird’s overall vibrant appearance.

The male mallard’s eyes are a deep, dark brown, and its legs and webbed feet are a striking orange.

The adult female mallard in breeding plumage is a stunning sight to behold. Her feathers are mottled brown, each displaying a sharp contrast ranging from buff to very dark brown, a trait shared by many female dabbling ducks. This coloration creates a beautiful, intricate pattern that seems to shimmer in the sunlight.

She has a dark crown and eye stripe, which frames her face and enhances her striking appearance. Her cheeks are a soft buff color, adding a touch of warmth to her overall appearance.

Her bill is a striking gray color with a subtle orange tinge and is expertly adapted for foraging in the water. Finally, the female mallard boasts a bright blue speculum on her wings, bordered by crisp white bands. This bold splash of color is a breathtaking sight to see as she takes flight.

Listen to the Mallard

Habitat & Range

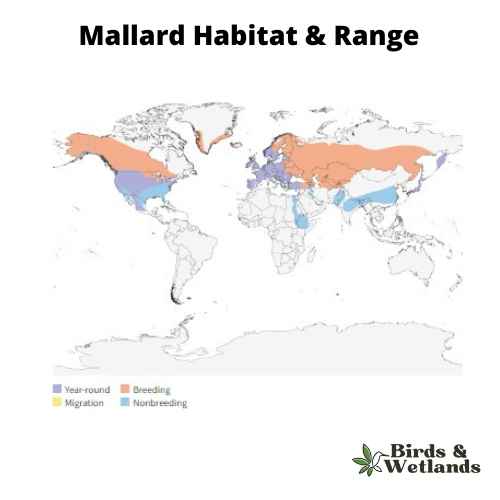

The mallard duck (Anas platyrhynchos) is one of the world’s most common and widely distributed dabbling ducks. It is found on every continent except Antarctica and is considered the ancestor of many domestic ducks.

Mallard ducks have a wide breeding range, covering much of North America, Europe, and Asia. They are also found in South and Central America, Africa, and Australia. These ducks are highly adaptable and can thrive in various environments, contributing to their success and widespread distribution.

In North America, their habitats often overlap with the several species such as the mottled duck, American black duck and Mexican duck.

During fall migration, mallards prefer areas with shallow sanctuaries and an abundance of aquatic plants, as these provide them with both food and shelter. They inhabit various habitats, including wetlands, shallow ponds, lakes, streams, rivers, and marshes.

They also use agricultural areas such as grain fields and irrigated pastures. In colder climates, they migrate south for the winter, but in more temperate climates, they are year-round residents.

In the summer, these ducks are found in prairie potholes and semi-open country.

Mallards are among the few wildlife species that have adapted well to urbanization and human-altered environments. As a highly adaptable species, these ducks have become permanent residents in temporary wetland habitats, city parks, golf courses and artificial lakes.

Mallard ducks are also generally successful at coexisting with humans, especially in urban and suburban areas. These ducks take advantage of the resources humans provide, such as food and water. As a result, mallards are often found near humans and are a common sight in many urban and suburban environments.

However, it is important to note that mallard ducks, like all wildlife, can sometimes cause problems for humans. For example, mallards may damage gardens or crops or cause conflicts with humans in other ways. In such cases, humans may need to manage or mitigate these conflicts, such as by using deterrents or fencing to protect gardens or crops.

Invasiveness

Mallards are considered invasive when found outside of their native range due to their ability to adapt easily and quickly to new environments. They have a natural tendency to disperse widely, and this, combined with their broad diet, can survive in various habitats.

Furthermore, mallards from feral populations exhibit aggressive behavior towards other waterbirds, which may lead to the displacement of native species. These birds are known for hybridizing with other ducks, such as domestic breeds, creating hybrid offsprings that can spread disease and outcompete the native population.

The rapid growth rate of mallards is another factor that contributes to their status as an invasive species. In some areas, mallard populations can double in size yearly if they can find sufficient food resources.

Mallard eggs have also been documented as hatching in shorter periods than native ducks, giving them a competitive advantage in terms of nesting success. Additionally, mallards often breed extensively near human settlements where there is little competition from other duck species.

Introducing mallards to native habitats of threatened and vulnerable duck species can hamper conservation efforts. These ducks are highly adaptable and drive the native species out of nesting and feeding areas.

Threats of Hybridization

Hybridization occurs when individuals of two different species breed and produce offspring, which can have a range of characteristics that are intermediate between those of the parent species.

In some cases, hybridization between mallards and indigenous duck species can lead to the extinction of indigenous waterfowl through a process known as genetic pollution.

This process occurs when the hybrids outcompete the indigenous species for resources, such as food and habitat, or when the hybrids mate with the indigenous species and produce offspring that are not viable or are less fit than the parent species.

As a result, the hybrid individuals may be more successful at reproducing and passing on their genes, leading to a decline in the number of purebred individuals of the indigenous species.

Another way that hybridization can contribute to the extinction of indigenous waterfowl is by creating hybrid offspring that are less adapted to their environment or have lower reproductive success.

For example, if the hybrid offspring are less able to find food or shelter or if they are less able to defend themselves against predators, they may be less likely to survive and reproduce. This can lead to a decline in the number of individuals of the indigenous species over time.

Hybridization is not the only threat to indigenous waterfowl. Its impact on these species can vary depending on the characteristics of the parent species, the environment they live in, and the presence of other threats. It’s worth noting that hybridization is just one of many potential dangers that indigenous waterfowl face.

Feeding Habits & Diet

Mallards are omnivorous, meaning they will eat a variety of plant and animal matter. Their diet consists largely of aquatic plants, seeds, grains, and insects in the wild. They will also occasionally consume small fish, snails, and other invertebrates.

In urban settings, mallards have been known to scavenge for human food, such as breadcrumbs and other scraps.

During the breeding season, mallards will switch to a more protein-rich diet to support the growth and development of their eggs and chicks. This may include more insects, snails, and other small animals.

Mallards are social birds and will often feed in large groups. This can lead to competition for food, especially in urban parks where resources may be limited. To avoid conflict, these wild ducks will often use a variety of vocalizations and body language to communicate and establish dominance within the group.

The mallard species has a unique feeding behavior known as “dabbling.” This involves the duck tipping its body forward and submerging its head underwater to reach for food.

Mallards can locate and extract food from the sediment at the bottom of ponds and other shallow water bodies using their sensitive bill and webbed feet.

Nesting & Mating Habits

The male and female mallards form monogamous pairs during the breeding season. However, extra-pair copulations occur, with several male mallards already belonging to a couple chasing after a single female. This affair is usually consensual, but mallard drakes are infamous for their unusual habit of forced copulation.

This breeding season typically lasts from February to June. During this time, males use their colorful feathers and courtship displays to attract mallard hens. Once they have found a partner, they will fly to the northern parts of their range. The females choose nest sites.

Mallards are known for their bowl-shaped nests, which these wild birds build using grasses or other vegetation as a lining material. These nests are typically built on the ground, hidden among thick vegetation or tree cavities to conceal them from predators.

On rare occasions, females may build their nests at higher elevations such as in hollow trees and on ledges.

The female mallards lay an average of 9 to 13 eggs per clutch, although this can range from 4 to 18. It takes about 27-28 days of incubation before the eggs hatch. During the incubation period, the male may leave the breeding areas to join other males at their molting areas.

The chicks are precocial and able to leave the nest soon after hatching. They can feed independently when their downy body is dry and swim shortly afterward.

Mallard ducklings remain close to the nest for the first two days following hatching but follow their mother for protection until their first flight at around 50 to 60 days old.

Threats & Conservation

The mallard duck is one of the world’s most successful bird species. They are found across much of the Northern Hemisphere. Despite their apparent success, mallards still face various threats that can seriously impact their populations.

Habitat loss is one of the primary threats facing mallards today. Wetlands are being drained and converted into farmland or urban areas, threatening the ducks’ natural habitats.

Another threat is competition with other dabbling ducks, such as Muscovy ducks or ruddy ducks, which can outcompete native ducks for food and other natural resources, reducing their numbers.

Pollution from agricultural runoff, oil spills and other sources also contribute to declining populations by contaminating nesting sites in wetland ponds and lakes where mallards feed and breed.

Mallards are not considered threatened due to their large range. However, they are still at risk in some areas due to local threats such as climate change, overhunting or habitat destruction.

To protect these iconic birds, many governments have taken steps to conserve wetlands that provide essential habitats for them. Some countries have enacted hunting regulations to allow only certain methods or times when hunting mallards is permitted to reduce population declines caused by overharvesting.

In addition, organizations like Ducks Unlimited work with landowners, government agencies and other conservation groups to protect wetlands across North America that provide critical breeding habitats for waterfowl such as Mallards.

Hunting

The mallard is the most hunted waterfowl in North America. Most states allow the hunting of mallards, but certain hunting regulations and limitations are in place to prevent overhunting.

Key Points

- Mallard ducks can adapt to various environments and habitats, making them one of the world’s most geographically widespread species of duck.

- The Mallard can be found in wetlands, rivers, streams, lakes, ponds, and marshes across North America, Europe, Asia, and Africa.

- Male mallards have iridescent heads with greenish sheen and bright yellow bills, while females are mostly grayish brown with orange-and-brown bills.

- Mallards have hefty bodies, flat bills and rounded heads.

- Mallards have adapted to living in close proximity to humans. They inhabit urban and suburban parks across the country.